Transforming Lives: Colombia’s New Approach to Women in the War on Drugs

In the midst of the bustling city of Bogota, Colombia, stories of struggle and hope emerge from the walls of Buen Pastor, the main women’s prison. Ana Tabares, a mother of two and a former worker in a cocaine laboratory, represents a poignant example of the human cost of the long-standing war on drugs in Colombia, the globe’s largest cocaine producer. Her story is not unique; it mirrors the experiences of thousands of women caught in the crossfire of an aggressive anti-drug campaign backed by decades of military force and financial support from international allies.

At 36, Tabares found her life irreversibly altered when law enforcement disrupted the operations of the remote camp that employed her. Despite her limited involvement, she faced a harsh sentence of nearly 11 years for narcotics trafficking and production – a stark testament to the relentless pursuit of individuals at every level of the drug trade, often sidelining the larger figures who continue to elude capture.

However, a transformative initiative is underway. In a marked departure from previous strategies, Colombia’s government under leftist President Gustavo Petro is challenging the status quo. Recognizing the inefficacy and immense human cost of decades-long policies centered around militarization and criminalization, Petro advocates for a paradigm shift towards decriminalization and prevention. “We need to decriminalize and reduce consumption through prevention, given the global failure of the war on drugs,” he declared, signaling an overhaul in how Colombia confronts its narco problem.

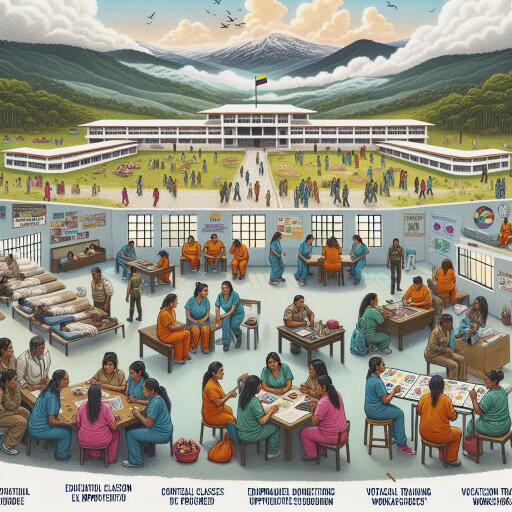

This reevaluation has materialized into tangible legislative change. In March 2023, a revolutionary law was enacted, enabling economically disadvantaged women, who serve as the primary caregivers for their families, to substitute traditional incarceration with community service, pending judicial approval. This reform seeks to alleviate the disproportionate impact of the war on drugs on women, particularly those incarcerated for minor roles in drug trafficking or distribution.

The statistics are revealing: approximately 37 percent of women in Colombia’s prisons are incarcerated for drug-related offenses, as opposed to only 15 percent of male inmates. The new law has already facilitated the release of several women, offering them a second chance at contributing positively to their communities and reuniting with their families.

For mothers like Tabares and Angie Hernandez, another inmate whose descent into drug addiction and subsequent involvement in small-scale trafficking led to years of separation from her children, this policy offers a glimmer of hope. Hernandez, like many others, yearns for the opportunity to rebuild her life and mend the bonds with her family strained by her incarceration.

The plight of these women and the broader issue of drug-related incarceration underscore a critical aspect of the drug war – its human toll. Reports from international bodies and NGOs highlight the significant percentage of women imprisoned for drug offenses throughout the region, most of whom are mothers, underscoring the far-reaching social repercussions of current drug policies.

As Colombia embarks on this new path, it sets a precedent for a more compassionate and effective approach to addressing the challenges posed by the drug trade. By shifting focus away from punitive measures and towards rehabilitation and societal reintegration, the hope is to not only transform the lives of those like Tabares and Hernandez but also to forge a more just and equitable society in the face of an enduring global issue.